Even though I have never met you, I know something very basic about you.

It is quite likely that you have had several experiences of beauty during your life. You have looked at a movie or a stunning landscape or the starry sky; you have listened to a song, you have watched a painting or a sculpture or a building, and you have perceived these as beautiful. The experience was highly satisfying.

So far my guess was pretty easy. Beauty is a "human universal", people in all cultures have had experiences of it, even though aesthetic criteria vary widely from culture to culture. But my interests is in what comes in the same package with this experience: because while you were having it, I surmise, you also thought: how good it would be if so and so (mate, son or daughter, parent, friend) could be here with me to enjoy what I am enjoying. How good it would be if he or she could participate in my experience. In other words, you wanted to share.

Beauty is for sharing. We have a deep need of enjoying beauty with another or several other human beings, because it in some way this validates it, makes it more intense, stronger and more significant. Sharing makes beauty more beautiful.

In this experience, we are likely to feel closer and more intimate with the person who partakes of it with us. We are together in a very special and unique space.

Which brings me to the subject of kindness. By kindness I do not mean only social courtesy, but a composite of several factors. In my book The Power of Kindness I have described eighteen components: sincerity, forgiveness, warmth, sense of belonging, contact, trust, empathy, attention, humility, patience, generosity, respect, flexibility, loyalty, memory, gratefulness, service, joy.

Kindness, in its many aspects, has been shown to affect us deeply, both when we are recipient of it and when we feel it and express it to other human beings. Studies show that some aspects of kindness, such as empathy, are deeply ingrained in the functioning of the human brain, and that the homo homini lupus philosophy – the traditional view that human beings are at war with each other and act only out of selfish motives, is false or at least largely imprecise and incomplete. We also know that altruistic and caring behaviors are widely present in many animal species, especially in such forms as a sense of fairness, empathy, mutual help, and warmth.

Kind people live longer and have better health; they are more succesful in their business, need less psychotherapy, are often fitter, and smoke less. Above all, kindness is an end in itself: it is experienced as valuable, independently of any ulterior benefits it may offer. In recent years more and more studies have shown that feelings and behaviors involved with kindness and care are not just socially learned coping patterns, or even defense mechanisms to protect us from feelings and impulses that are incompatible with our self-image, but are authentic, spontaneous needs and emotions springing from the depth of our being. They can also be seen as attitudes which have helped us human beings survive in the course of our evolution. The idea that kindness is a fundamental inborn human trait is crucial to a fair and thorough understanding of human nature.

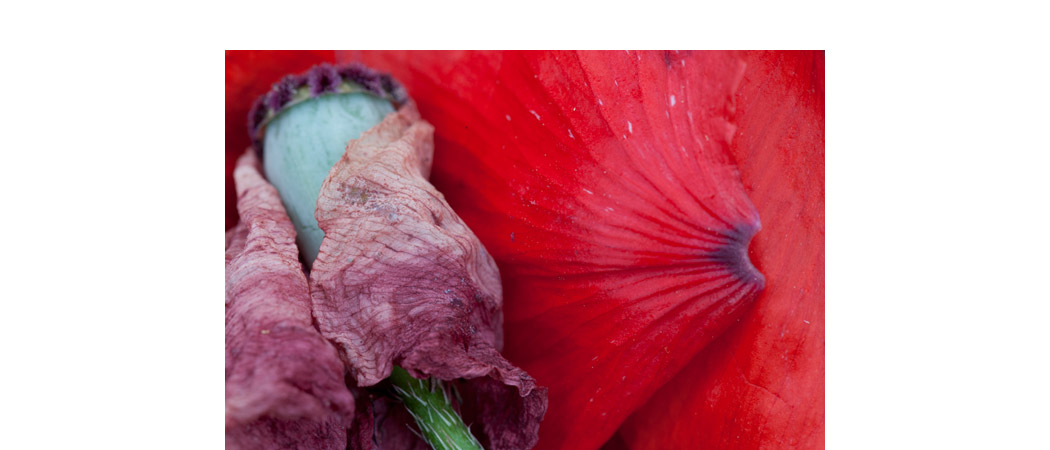

Beauty, by facilitating empathy and intimacy, makes us "kinder". Beauty is often associated with competition, richness, exclusiveness, and envy. It is also linked to jealousy, compulsive cosmetics, fear of aging. But the experience of beauty itself is freeing, nourishing, uplifting, and transforming. I am talking about the beauty we may find in a great variety of contexts: in nature, at a concert, at an exhibition. Also in everyday situations: we may find beauty in the reflections of the sun on a piece of metal, or in the shape of a fallen leaf, or in the pitter-patter of the rain. Most important, there is such a thing as inner beauty: for example, the beauty of intelligence, of caring and generosity, of vivaciousness and humour.

"Beauty" has rarely been researched as such. The word is too general and vague, and it sounds old-fashioned to many. However, an ample volume of research shows that more specific activities manifestly connected with the aesthetic dimension of life, such as learning a musical instrument, spending time in nature, going to an exhibition, reading a book, producing a painting, singing, doing drama, are highly beneficial to physical and mental health. Studies show that art schools benefit academic performance in all fields, stimulate intelligence and liveliness, increase self esteem and evoke prosocial attitudes and behavior. Students in art schools not only do better at school, they also participate more in community activities, and are readier to do a friend a favour. We now know that participating in cultural events, such as art shows, theatre or concerts, makes people enjoy greater health and satisfaction in life.

In the past few years I have investigated the effects beauty has on the human psyche, both through my own work as a psychotherapist, and by interviewing a variety of individuals. The results are extremely encouraging, and show that beauty in all its aspects is a readily available resource to all. There may exist something we could call "aesthetic intelligence"- the capacity to appreciate beauty - which can be cultivated and developed.

Unfortunately, for a variety of cultural and historical reasons, beauty is underrated; it is not appreciated to its full potential, and at school is often presented in ways that are boring, too rigid and abstract. Many people think that in order to appreciate beauty you must be highly cultured, or need money to afford great works of art in your home or expensive travels to exclusive resorts; or, deep down, they may feel they do not deserve it: they feel threatened by the extremely powerful effects the experience of beauty might have on their personality.

One important benefit of the aesthetic experience is that it can move us powerfully, thus helping us to shed our masks and roles, and get in touch with more authentic elements of our being. Once we have at least partly outgrown limited models of beauty – consumerism, possessiveness, competitiveness, preoccupation with physical appearance, materialism, stereotyping, cultural clichés, preconceived preferences – we can learn to develop our aesthetic intelligence, both in its range and in its intensity.

As I have mentioned, beauty shared with other people is felt more strongly and enjoyed more. The experience of beauty makes us open, spontaneous, empathic. In such a state we are more drawn to altruistic attitudes and behavior. But there is another reason beauty why makes us kinder, and it has to do with needs. Are your needs satisfied? The question is not as simple as it may seem at first. The reason is that our society is continually creating new needs: for gadgets, clothing, travels, cars, food, and so on. Most if not all of these are not strictly necessary for survival, yet powerful advertising and social pressures turn them into acquisitions not only desirable, but indispensable. These are clearly artificial needs, and our whole economy depends on that. I will not discuss here the issue whether this is morally right or not. What concerns me here is that creating new artificial needs can distract us from the fulfilment of needs that are not so explicit, but are indeed more profound and basic to our nature. Take the need for beauty. I strongly believe that we need beauty in its many forms, and that when it is missing from our life, we are in trouble: we feel irritated, nervous, uneasy, or even panicky or depressed. The need may be so deeply buried that we are unaware of why we are so upset.

Much of my time as a psychotherapist is devoted to helping people to treat themselves better. They need, for instance, solitude and silence, or nature, or time for play, or greater appreciation from others, and the chance to express themselves. And they need beauty. But they do not know it, in much the same way as some of usas some of us can go without enough sleep or water, yet not feel thirsty or sleepy. And yet the need is there - and if it remains unfulfilled, we feel uncomfortable. As we know, the moment we are satisfied and our needs, including the deeper ones, are met, we feel at peace and are better disposed to the world.

We do not become kinder by trying hard to be kinder, or by making and effort to suppress or sacrifice what we are and what we feel. Rather, it is through a form of wise benevolence towards ourselves. It is an easier and much more elementary way: enjoy beauty and you will be happier. Be happier and you will be kinder.

Does Beauty Make Us Kinder?

First Published in www.envisionkindness.org